Fjorent Rrushi

Head of ALM & Research at Raiffeisen Bank Albania

The EU enlargement process has stalled considerably. This can be clearly deduced from the chronological order of enlargements. Since the founding of the EU in 1958, new members have joined approximately every five to ten years after the first enlargement in 1973. The 1973 enlargement was followed by EU accessions in 1981, 1986, 1995 (including Austria), 2004 and 2007 (including CE countries plus Bulgaria and Romania). Finally, Croatia joined the EU in 2013 as last incoming country before the first departure from the EU (Brexit 2020). Currently, it looks like no further candidate country will be able to fully join the EU before at least 2030. This looks like the longest pause in EU enlargement in its history, possibly lasting 20 years. It seems all the more ironic that the EU wants to give not only the countries of the Western Balkans (as it has since 2003) a further EU perspective, but now also Ukraine (plus Moldova and possibly Georgia). Many things do not fit together here. In the following, we try to put things in order and point out perspectives.

The EU (enlargement) summit end of June (incl. an EU-Western Balkans leaders’ meeting) has an extremely bittersweet aftertaste for the CEE region. With the official accession candidate status for Ukraine and Moldova, the EU has come to a more concrete enlargement perspective for these two countries. Such a move was possibly factually and morally unavoidable. At the same time, the EU enlargement to the Western Balkans continues to falter, as it has for years and now. Compared to Ukraine and Moldova, Bosnia has not been granted official candidate status yet, Albania and Northern Macedonia were only this week allowed to finally start EU entry negotiations because of internal EU blockades and leadership weaknesses. The EU accession negotiations of Montenegro and Serbia are stuck in nowhere since 2012/2013. In some cases, not only disappointment with EU enlargement, but alienation is recognizable in the Western Balkans. And that is exactly what must be avoided in the case of Ukraine. Just as in Bosnia the political process was partly ignited by external actors, this could also happen in Ukraine. And this especially if there are weaknesses in the EU accession process. Russia will actively eye political and economic (or military?) successes of the new EU candidate Ukraine. Any (supposed) failures or lack of progress in EU agendas will certainly be actively addressed by the Russian side. In this respect, granting EU candidate status should by no means be understood “only” as a short-term fix and political signal to provide Ukraine with political tailwind and moral support. In light of geopolitics the EU candidate status is now a matter of developing an EU-driven economic development and modernization agenda for Ukraine (and Moldova), as the EU has done with the Economic and Investment Plan for the Western Balkans.

There is optimism that underneath things are moving. We might see some concrete progress later in the course of 2022. The Bulgarian parliament vote on lifting the veto on North Macedonia under certain conditions goes in the right direction. Finally, lawmakers in North Macedonia voted with a majority of votes for the French-brokered proposal that shall settle the dispute with Bulgaria. That there is a lot going on in EU enlargement issues is shown by the commitment of France here – otherwise traditionally not a pro-enlargement actor at all. Even for other countries in the region such as Bosnia and Herzegovina or Kosovo the plate is not completely empty. The agreement brokered between the EU and all key Bosnian political parties in June seem to have paved the road to a positive outcome for a candidate status to be granted for Bosnia by the end of 2022 — if milestones are reached (especially in the areas of rule of Law and Judiciary reforms outlined in the Agreement). It is indicative that in such difficult times the Republika Srpska moved away from total confrontation with Western countries and signed an agreement with EU politicians together with other political parties. Thus, it seems that there is a look West rather than East.

Although the youngest country in Europe, Kosovo demonstrated that the democratic environment is lively with competitive and accepted elections, a rarity in this corner of Europe. Progress made on the democratic front and the improvement in democratic indices has not been rewarded yet by the EU. In our opinion the EU wants to exert pressure on the government in Kosovo to extract some concessions on a final agreement with Serbia. That said the EU could already offer Kosovo visa liberalization as a gesture to bring the country closer, as it remains the only Western Balkan country to have such restrictions. Candidate status may follow later.

The (potential) enlargement to the Western Balkans is already seen as a substantial challenge at EU level. This is especially true at the political level and in terms of voting procedures; it is less so in terms of population and economic power. In this respect, we believe it makes sense to actively link the EU enlargement to the Western Balkans with the internal reform of EU voting mechanisms. In this way, the EU would put itself under meaningful pressure and not “only” the enlargement candidates. It would therefore be expedient to agree on both, an EU reform and enlargement target date or time corridor (e.g. 2027-2030). We think that such a long-term ambition fits well with the comprehensive mission- and vision-oriented EU policy orientation in other areas (such as green transformation). In this respect, it is clear that only when the Western Balkan (or parts of it) is integrated into the EU and the EU will manage to reform its internal coordination mechanisms and demonstrates more geopolitical problem-solving competence (plus corresponding pragmatism) the EU can really turn its attention to the accession candidate Ukraine or other (potential) accession candidates.

After many years of fast economic growth, some Western Balkan countries’ convergence towards the EU has stalled. Even more astonishing is the contrast with other CE/SEE countries that are now EU members. This demonstrates how important the EU integration has been in economic terms and what a powerful driving force the economic integration could be. It’s therefore of paramount importance in our opinion to deliver an overhaul of the EU funding for negotiating countries, i.e. to provide substantive EU funding and cooperation with EU institutions here ahead of final EU membership. An Austrian policy proposal (having the backing of some other member states, like indicated recently by Slovenia) that goes in this direction is very important. If countries make progress by closing chapters of the EU accession negotiation it would be very important that they are somehow integrated in the EU (financing) programs that concern those chapters. This would have a tangible impact on the population of the Western Balkan countries as well as on the preparation of these countries to be ready when they become full members. Participation in EU meetings with a special status without voting rights, involvement in the preparation of policies could speed up the process of convergence and render these countries more ready when full membership comes.

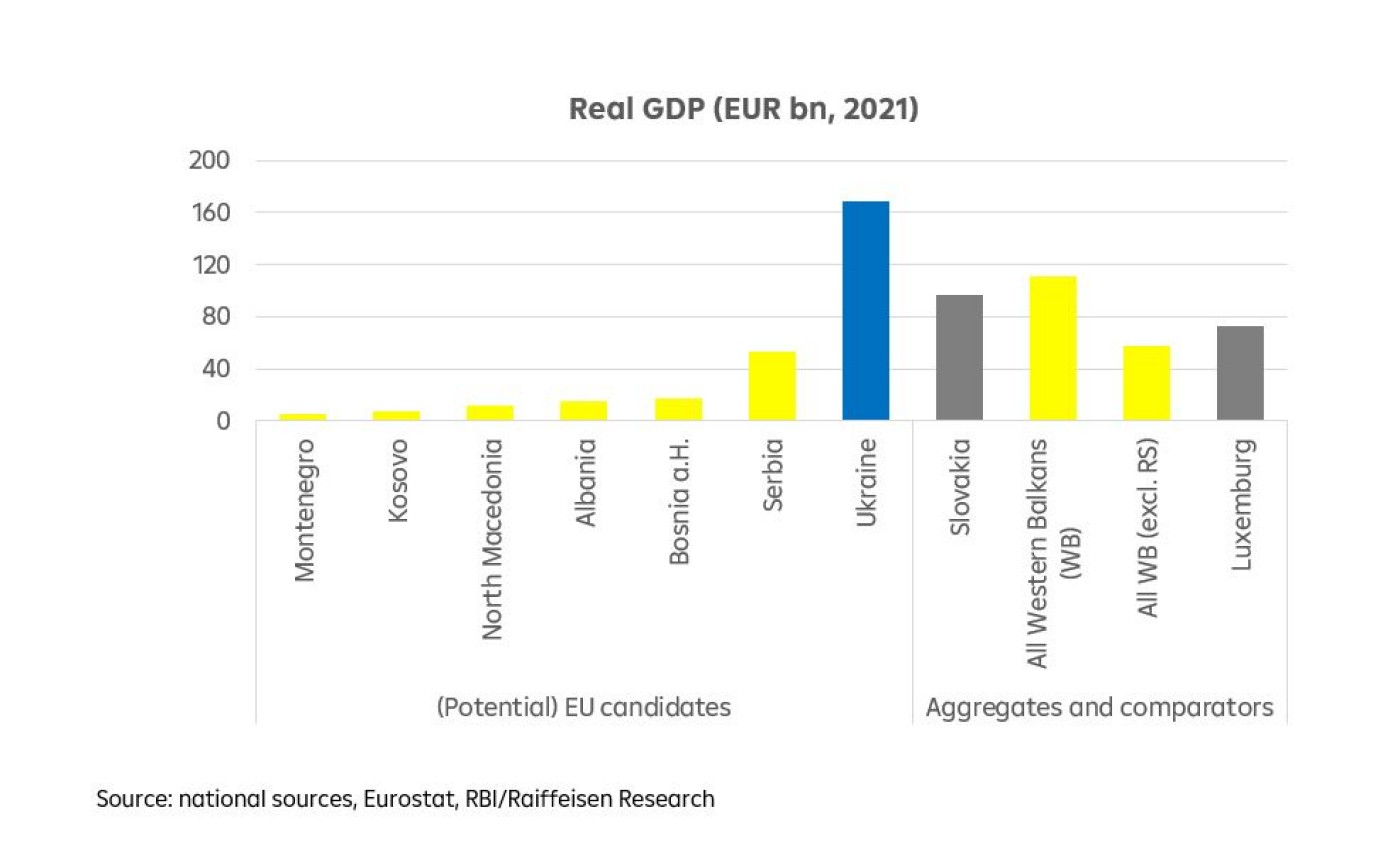

There was also a (geo-)strategic view of earlier enlargement rounds (e.g. Spain, Portugal, Central Europe). In recent years, there has been a feeling that the EU accession process is sinking into the small-small. And on the surface, the Western Balkans are small. We are talking about an economic power of just over EUR 100 billion, which puts the Western Balkans between Slovakia and Luxembourg! But there is more at stake here. In the Western Balkans, there is an active competition of rising interests with Russia, China and, to some extent, Turkey. Even though the geopolitical challenge or confrontation may be smaller on the Western Balkans than in case of Ukraine, the EU could show geopolitical problem-solving competence here with relatively little effort or risk attached. This issue should also be accepted by countries that are traditionally more skeptical about EU enlargement. But the EU has not yet arrived at a geopolitical view of the Western Balkans. In the recent frictions in Bosnia and Herzegovina, one once again had the unfortunate impression that the USA and the UK have played the geostrategic and sanctions agendas more strongly than the EU (once again due to internal blockades within the EU).

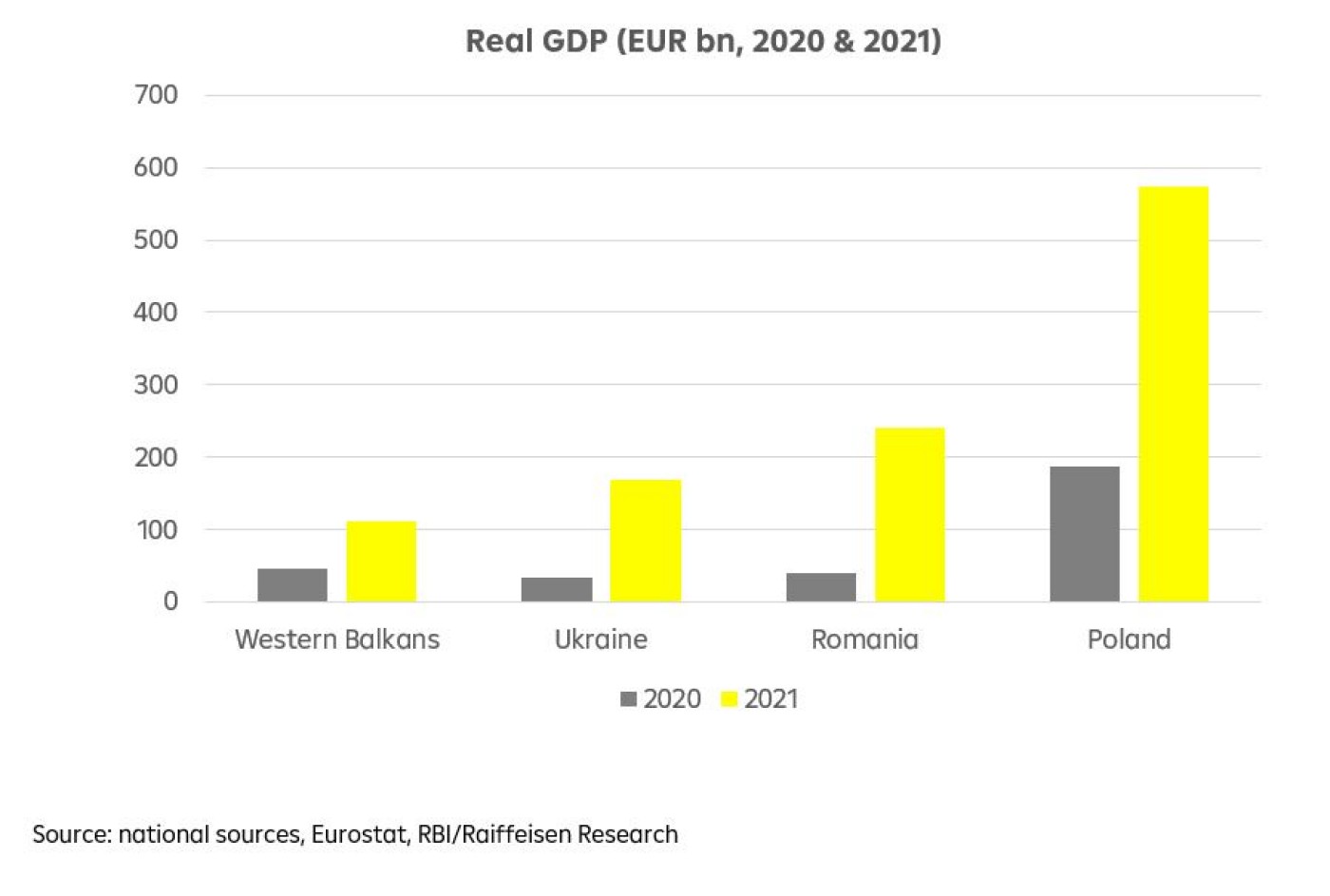

Moreover, with new EU enlargement candidates, the EU’s enlargement agenda will remain an essential and (geo-)strategic policy field for decades to come. Before the emergence of new EU candidates out of the post-Soviet space, there was a chance that the EU accession agenda — after a potential entry of the Western Balkans — might have been put aside or even closed down. Possibly, the very slow EU accession process of Turkey (a candidate at least as challenging as Ukraine) could have come to an end in this way. Now a return to serious negotiations cannot be ruled out in the coming decades with the EU accession into the post-Soviet space likely being a long-lasting and complicated process. It should be noted that Russia will probably actively exploit any weaknesses in the EU enlargement process (with regard to the Western Balkans and/or new candidates) propagandistically in the future in order to showcase a presumed “weakness” of the EU. Incidentally, the same can be expected if individual EU countries will actively block the opening of official accession talks of Ukraine (or other candidates) at some point in the future. In this respect, the EU must also learn sensible power politics internally and, as shown earlier, strengthen its own capacity to act. And a further accession of Ukraine to the EU will of course have substantial geopolitical and economic implications for the EU. If Ukraine succeeds in embarking on a successful long-term transformation path like Poland or Romania, it could become an economy with a GDP weight of at least EUR 600-800 billion in 10-15 years.

Head of ALM & Research at Raiffeisen Bank Albania

Chief Economic Analyst and Research and Advisory Group Manager at Raiffeisen Bank Bosnia and Herzegovina

Head of Research in Raiffeisen Bank Ukraine

Head of Research RBI AG in Vienna

Do you also have a travel tip, a recipe recommendation, useful business customs, interesting traditions or a story about CEE that you would like to share? Write to communications@rbinternational.com and share your experience.