Basel III

Why was Basel III introduced?

The liquidity and capital adequacy guidelines for banks are a direct consequence of the global financial crisis in 2008 and 2009. The guidelines are intended to reassert the liability principle. During the financial crisis, it had become apparent that most credit institutions did not have sufficient equity and liquidity to cover the risks associated with lending. The Basel III Framework is intended to ensure the stability of the financial markets in the future and to reduce, and in the best case avoid altogether, the burdens on governments, i.e., taxpayers, from aid packages and rescue packages for banks and other credit institutions.

Implementation of the Basel Liquidity- and Capital Requirements Directives in Europe

At the European level, the new directives were implemented based on the EU regulations Capital Requirements Directive (CRD IV) and Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR). The EU Regulation CRR is aimed at credit institutions while the EU Directive CRD IV contains the requirements that are important for the EU member states as well as specifications for the licensing and supervision of financial service providers. In addition, it contains the sanctions provided for in the event of infringements of the regulations.

Basel Framework in a nutshell:

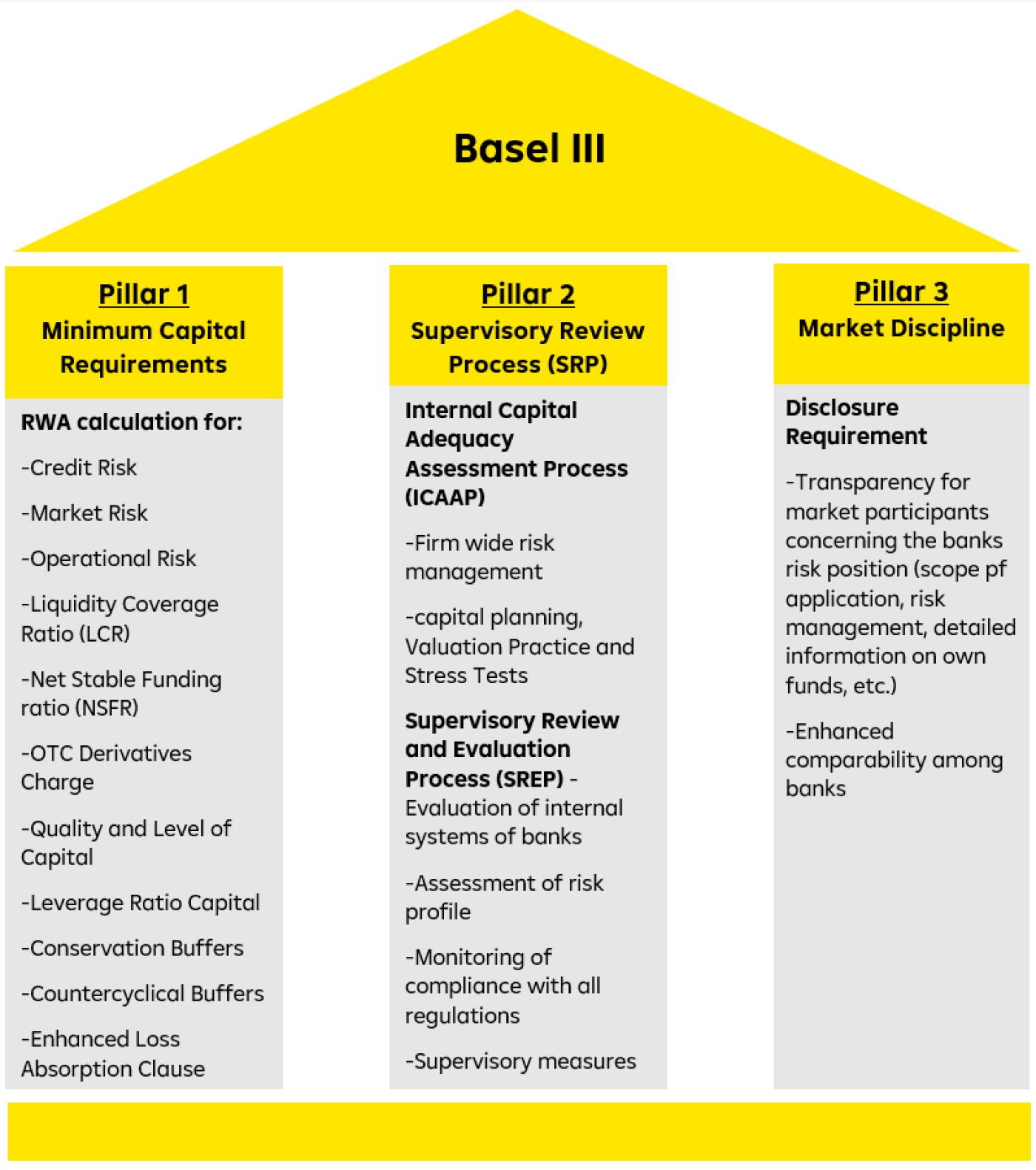

Pillar 1: Minimum Capital Requirements —defines the eligible own funds and the approaches used to determine the minimum own funds for credit and market risks as well as for operational risks.

Pillar 2: Supervisory Review Process (SRP) — the establishment of suitable risk management systems in banks and their review by the supervisory authority.

Pillar 3: Market Discipline — increased transparency due to expanded disclosure requirements for banks.

Basel 3 Finalization

While the Basel frameworks have been focused on credit risk, market risk and operational risk, new types of risk, or at least drivers for it, are emerging due to ongoing climate change. These environmental, social and governance, oftentimes referred to as ESG risks, are now also considered by the COM in its proposal. ESG risks may negatively affect financial institutions’ assets in various ways. One could think of a direct negative impact of natural disasters such as earthquakes in the form of damage to buildings of banks. Banks’ customers might also be negatively impacted by climate change, for example by disrupted water supply to crucial production sites of companies, which could result in higher loan defaults. The previously mentioned risks are physical risks. Furthermore, banks can also be negatively affected by transition risk such as changes to demand and supply mechanisms or the introduction of new taxes on unsustainable activities.

As ESG risks become a new risk driver throughout the banking industry, it can be expected that there will be a supervisory response as to how to incorporate such ESG risks into the risk-based capital framework. The European Banking Authority (EBA) has been mandated with assessing whether a dedicated prudential treatment of exposures related to assets or activities associated with environmental and/or social objectives would be justified. Under the released proposals of Basel III Finalisation, the deadline of EBA’s mandate to submit its report has been brought forward by 2 years from June 2025 to June 2023. This illustrates the urgency of clarifying how the sustainability of exposures of banks is to be reflected in the regulatory capital requirements, e.g. a ‘green’ supporting factor or ‘brown’ penalizing factor might potentially support the capital allocation of banks in line with EU’s sustainability objectives as it would encourage lending for ‘green’ initiatives and would incentivize banks to increase their exposures to such assets.

Additionally, new provisions and adjustments are made to address the significant risks credit institutions will face due to climate change and economic transformation:

- systemic risk buffer may be used on subsets of exposure subject to physical and transition risks,

- short medium- and long-term horizons on ESG risks have to be considered in the ICAAP,

- a requirement for concrete plans to address ESG risks is introduced,

- a sustainability dimension is introduced to the prudential framework to incentive allocation of funding across sustainable projects.

- EBA will draft guidelines on uniform integration of ESG risks in SREP and ESG stress testing and in addition a concrete supervisory power to address ESG risks is added.

The ECB economy-wide climate stress test published on 22 September 2021 sheds light on the previously missing link between ESG risks and credit risks. Especially in the context of transition risk, carbon-intense industries, such as mining or electricity, would incur considerable cost to either reduce CO2 emissions or to participate in emissions trading to offset emissions. According to ECB, this significant cost increase could lead to an increased probability of default over the short- to medium-term.

You see there is a lot to do on ESG risks before the really exciting questions will be answered: will there be a green incentivizing factor bringing down risk weights for ‘green’ assets or a ‘brown’ disincentivizing factor increasing risk weights for ‘brown assets? Our understanding is that first the uniform definition for ‘green’ according to the EU Taxonomy must be rolled out. Based on these regulators and supervisors will see, what the potential impact of lowering/increasing the risk weights might be. This will take at least 2 to 3 years before reasonable, comparable numbers are available.

For inquiries please contact:

regulatory-advisory@rbinternational.com

RBI Regulatory Advisory

Raiffeisen Bank International AG | Member of RBI Group | Am Stadtpark 9, 1030 Vienna, Austria | Tel: +43 1 71707 - 5923